You may have heard of, or tried some of the various DNA kits going around today, like 23andMe, Everlywell and GenoPalate. These test kits claim to tell you what foods you are sensitive to, health conditions you are predisposed to, and even what lifestyles are most beneficial to you. But how does genome analysis work and are these tests accurate?

What is DNA?

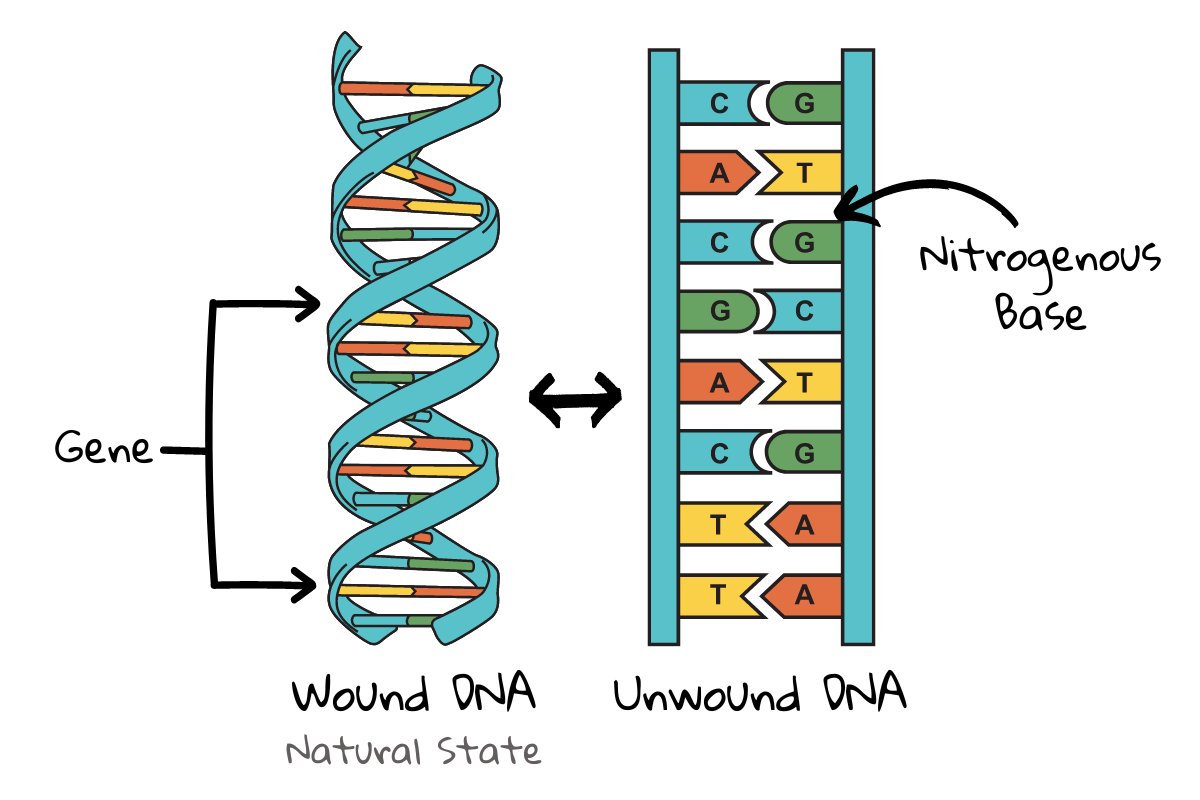

DNA is the blueprint of who you are from your brain to your pinky toe. The molecule, DNA, is shaped similarly to a ladder when untwisted. What would essentially be the “rungs” of this ladder are called nitrogenous bases. The order of these bases are then “read” by our body like an instruction manual. Our DNA is segregated into specific regions called genes. Each gene contains a unique set of “directions” for building a certain machinery in our body. The “instruction manual” itself, which contains all of our genes, is called the genome.

A majority of human genes are “written” the same way from person to person. However, sometimes a portion of our DNA can change, break-off, or duplicate and the instructions our body follows become tweaked ever so slightly. This is known as a mutation and it is the basis of human diversity. Mutations are what create the plethora of diverging observable characteristics, ranging from eye color to inherited diseases.

How do we study the human genome?

Scientists have been studying genomes for years. Gregor Mendel first discovered the pattern of basic inheritance with his famous pea breeding experiments. These experiments paved the way for many more selective breeding studies- furthering our understanding of more complicated methods of inheritance.

In 1990, scientists were given around $3 billion from United States agencies and 15 years to complete the decoding of the entire human genome. The goal of the Human Genome Project was to sequence and understand what the jumbled combinations of this complicated hereditary information meant from just a handful of volunteers. Surprisingly, the scientists were able to sequence 97% of the human genome accurately in 13 years. Today, we know 100% of the order of bases within our DNA, otherwise known as our DNA sequence. Even with these discoveries, we are still piecing together the meaning behind this sequence and which mutations correspond to a particular trait or disease.

So what can we learn from our genome?

Our genome holds the ability to tell us quite a bit about our bodies, but it is still early in our research. We have learned some useful things so far like the inheritance of several diseases, how to identify individuals and trace lineages, and even predict various traits of future children. But there is far more to unearth.

Many diseases have not yet been traced back to specific genes. However, there are a small number of diseases- known as Mendelian diseases- that we can understand because they are caused by a mutation in only one gene. These diseases include Huntington's disease, sickle cell disease, and several others. Geneticists can predict risks of obtaining single-gene diseases because their inheritance follows a traceable lineage.

On the other hand, many more common and complicated diseases are proving too difficult to understand with our current knowledge. Scientists hypothesize that conditions such as high blood pressure, cancer, and diabetes could be controlled by several different genes as well as environmental factors- creating a complicated web. That is not to say that we will never have the answer. There is still much of the human genome that remains a mystery and scientists are uncovering new information as we speak.

The integration of genetic studies into the field of nutrition can also be beneficial in understanding human health. So, what can our genome actually tell us about our diet and nutrition today? Not much, unfortunately. But do not be discouraged, there are several genes scientists have identified that affect nutrition and we can learn a bit from that. For instance, there is a version of one specific gene that can increase your susceptibility to vitamin C deficiency. While a mutation in a separate gene can raise your risk of hypertension with a higher sodium intake than normal.

Two fields combining nutrition and genetics show promise for exciting health benefits. The first is nutrigenetics, which focuses on how different versions of genes control the way our body responds to different nutrients. The second field is called nutrigenomics and it focuses mainly on how chemicals from certain foods affect what genes are expressed and which are not. Much is unknown in this field of studies as nutritionists and geneticists begin to collaborate more than ever before. However, various case studies have furthered our understanding of these concepts. One study found that a certain gene variant was associated with vitamin D deficiency. Research similar to this can help you understand your genetic susceptibility to conditions like vitamin D deficiency. Even though there is much to uncover in the realm of nutrigenetics and nutrigenomics, what we do know can help us better understand what constitutes a “good” diet. Understanding our diet can lead to longer life-spans and lower our risk for common diseases like obesity and cardiovascular disease. You can use Guava to monitor important biomarkers, like cholesterol and blood sugar, to help prevent your chances of nutritional related diseases.

From the Human Genome Project we have learned more about our genes than ever before, and yet we have barely scratched the surface.

Does that mean at-home DNA test kits provide useful results?

Unfortunately, you should not expect to see significant medical or lifestyle breakthroughs from buying a home genetics test. While the test can be fun and may provide some direction in the realm of wellness, our new genetic knowledge does not mean that DNA test kits can tell you everything about your health. Yes, we have far more ability to analyze our own genome than ever before due to new technology and the decreasing costs of genome analysis. However, our knowledge of the genome is constantly changing, and on top of that, many at-home kits only sequence a small portion of our DNA. Still, there are plenty of tests today, such as Nebula and Sequencing, that will sequence your entire genome. They are generally more expensive, but the benefit of these tests is, as more research comes out, you can keep learning about your individual genome because you aren't just looking at a snapshot of it.

Can these tests tell you if you are predisposed to certain diseases?

Yes and no. Many diseases are far too complicated to be predicted by at-home DNA testing. It cannot tell you about the majority of human diseases and the fear is that these tests can be almost misleading when faced with the reality of how small the list of accurately predictable diseases currently is. Secondly, even though scientists have an approximation of some disease-causing gene sequences, this field of research is constantly changing. Therefore, the risks reported by at-home DNA tests can be inaccurate when based on outdated research. That being said, these tests can accurately tell you if you are predisposed to the diseases they test for, which are primarily Mendelian ones, if done correctly. But even if you have the variant of a gene for a certain disease, it does not necessarily mean you will develop this disease. Chance and environmental factors also play a role, so it is best to take preventative measures if you are predisposed.

Can these tests be used to personalize nutrition?

Again, it's complicated. The usefulness of these tests in the realm of personalized nutrition is widely debated. On one hand, many believe that giving people personalized dietary advice could make them more inclined to follow the recommended dietary changes, even if sometimes inaccurate. One study conducted at the University of Toronto found that people who had genetic tests advise them on ways they could personally improve their health were more likely to make these changes than those who received the same information presented as general nutritional advice. On the other hand, others worry that presenting nutrition guidance on just a genetic basis can lead to complacency in other factors that influence their health, like sleep and exercise. One study, known as the PREDICT study, conducted by King's College and Harvard Medical School, found that identical twins responded differently to identical dietary approaches. This confirmed that nutrition is affected by far more than just your genetics.

The controversy behind these tests has been ongoing. One side claims there is a certain right people have to know their own genomics and that seeing this information can encourage the public to make healthier choices in the future. While others claim these tests could cause unnecessary health concerns and ethical implications on the basis of genomic discrimination. As a result, several countries have begun to regulate these at-home tests. In 2008, the state of California tried to ban at-home DNA test kits. Multiple European countries have imposed regulations and bans as well. Furthermore, many have pushed to regulate advertisements for at-home DNA tests. This was after the Government Accountability Office and the Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention (EGAPP) conducted a study that found the benefits of these tests were listed on their websites an average of six times more than their risks and limitations. All of this information shouldn't necessarily deter you from these tests. There are useful at-home DNA kits out there that can tell us a lot about our genome. Additionally, as we speak, more is being uncovered about our genetics and new research has the potential to shine more light on your results. As always, it is important to do your research and consult a genetic professional or primary care provider to help sift through what is fake and what is fact in the field of genetics.

Ultimately, if you plan to use these tests, it's good to take the results with a grain of salt, because the human genome is far more complicated to analyze than swabbing the inside of your cheek.

Sources

- Shetty. (2008). Home DNA test kits cause controversy. The Lancet (British Edition), 371(9626), 1739-1740. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60745-X

- Finkel. (2012). The genome generation (1st ed.). Melbourne University Press.

- Alpert. (2016). Nutrigenetics and Nutrigenomic Is Changing the Field of Nutrition. Home Health Care Management & Practice, 28(1), 73-75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1084822314568343

- Fenech, El-Sohemy, A., Cahill, L., Ferguson, L. R., French, T.-A. C., Tai, E. S., Milner, J., Koh, W.-P., Xie, L., Zucker, M., Buckley, M., Cosgrove, L., Lockett, T., Fung, K. Y., & Head, R. (2011). Nutrigenetics and Nutrigenomics: Viewpoints on the Current Status and Applications in Nutrition Research and Practice. Journal of Nutrigenetics and Nutrigenomics, 4(2), 69-89. https://doi.org/10.1159/000327772

- Nielsen, & El-Sohemy, A. (2014). Disclosure of genetic information and change in dietary intake: a randomized controlled trial. PloS One, 9(11), e112665-e112665. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0112665

- Reinagel, M. (2019). Personalized Nutrition: The Latest on DNA-Based Diets. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/personalized-nutrition-the-latest-on-dna-based-diets/

- Singleton, Erby, L. H., Foisie, K. V., & Kaphingst, K. A. (2011). Informed Choice in Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Testing (DTCGT) Websites: A Content Analysis of Benefits, Risks, and Limitations. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 21(3), 433-439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-011-9474-6

- Cornelis MC, El-Sohemy A. Coffee, caffeine, and coronary heart disease. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2007 Feb;18(1):13-9. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3280127b04. PMID: 17218826.

- Rutherford, A. (2018). How Accurate Are Online DNA Tests? Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-accurate-are-online-dna-tests/

- Yu, Li, X., Wang, Y., Mao, Z., Xie, Y., Zhang, L., Wang, C., & Li, W. (2019). Family-based Association between Allele T of rs4646536 in CYP27B1 and vitamin D deficiency. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis, 33(6), e22898-n/a. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.22898