You might think, like many others, that hormones are the only major players changing throughout the menstrual cycle. Sure, there are bodily changes, such as the shedding of the endometrial lining and the all-too-familiar mood swings that come with it. But what about the physical changes happening in your brain?

In October 2023, a research study out of the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB) found that the entirety of women’s brain structure actually fluctuates throughout the menstrual cycle as well. As a biopsychology student at UCSB, I had the privilege of interviewing Elizabeth Rizor, a PhD candidate in Scott Grafton's Action Laboratory who authored this study.

As we sat down amidst the hum of UCSB's bustling campus, Elizabeth shared a rare glimpse into the relationship between hormonal health and brain structure. We also discussed how this research could redefine our current understanding of women’s health in areas like menstrual symptoms and exercise.

To start, I asked Elizabeth to help us understand the body parts and processes that were tracked—specifically brain matter and the female hormonal cycle.

There’s lots of gray area in our brains—but even more white area.

The building blocks of our brains are gray and white matter. Gray matter is typically the main focus of research since it's responsible for daily functions like controlling movement, memory, and emotions.

Gray matter is the outer layer of the brain, and as Elizabeth described:

“It’s like a cortical ribbon that goes along the edge of the brain. Gray matter is where functional activation is happening. It’s where the cell bodies [of brain cells, or neurons] are really clustered.”

About 40% of the brain is gray matter, while the other 60% is white matter. If white matter makes up over half of our brain, then it must also have a pretty important role.

Why is white matter white? Myelin wraps around the axons of brain cells which are the long cable-like connections between cell bodies. Myelin helps increase the rate at which electrical signals travel across the brain. When white matter is compromised, this can affect sensory, motor, and cognitive functions (basically the ability to sense, move, and think).

Elizabeth described that,

“white matter is the fatty tissue underneath the outer layer of gray matter. You can think of it like bundles of straws, or highways that transmit information between the different brain regions in the gray matter. It can perform long-range, cross-communication between the different areas in the brain.”

It seems that white matter is the vital medium for messages to be sent across different parts of the brain. If these areas are changing, this could imply changes in communication. The potential impact of this on women’s cognition, emotion, and overall brain function is still being investigated.

What do we already know about white matter?

What has been observed is that white matter changes across hormonal transition phases like puberty, taking birth control, menopausal treatment, and gender transition treatment — however, there is a lack of research exploring standard, baseline hormonal, and brain changes across a natural menstrual cycle.

Rizor and her colleagues noticed this lack of research in naturally cycling young women, many of whom will cycle for decades of their lives.

So, let’s get into the details.

The study included thirty women ranging between 18 to 29 years old. Their average cycle length was 31 days.

The hormones they tracked are a part of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. The word axis here refers to how these organs span across the body. Brain scans and hormone levels were analyzed at three time points throughout the menstrual cycle: menses, ovulation, and mid-luteal.

A tale as old as time: progesterone, FSH, and brain matter

After all of the brain scans and blood tests collected, the researchers found that follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and progesterone had a see-saw relationship. FSH was moderately high during menses and again during ovulation. Progesterone was then higher during the luteal phase, which is the tail end of the cycle.

But this wasn’t news to Rizor and her labmates. The big shocker, Elizabeth explained, was that,

“Both white and gray matter had opposing tensions between the two hormones. Where one was correlated with changes in white matter, the other correlated with the opposite. The same occurred with gray matter and cortical thickness.”

Cortical thickness is a measure of gray matter cortical ribbon width. You can think of this as a ribbon that’s wrapped around the white matter in your brain. Measuring changes in its thickness can tell us about brain network organization and even predict clinical symptoms in certain cases, like Alzheimer’s.

Okay, so hormones change my brain’s thickness? But what does that mean?

While this study didn’t focus on the cognitive changes that may come with cyclical changes in brain matter, there still may be certain advantages associated with each phase. Menstrual phase-dependent brain changes could provide an explanation for differences in emotional processing, cognitive performance, and motivation throughout the menstrual cycle that are being looked into today.

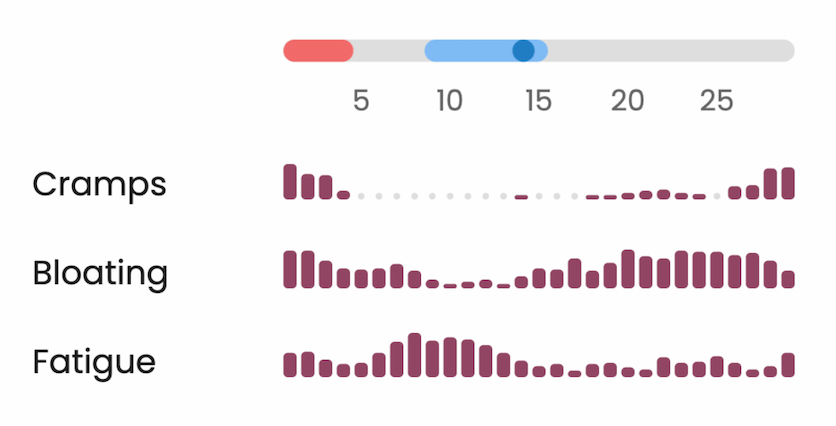

Studies like this provide an understanding of baseline, biological changes for further investigation of menstrual disorders, like endometriosis, premenstrual syndrome (PMS), and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). Some with these disorders have reported “difficulty concentrating and impaired work productivity” during the late luteal phase.

More and more research has found differences in attention, memory, and verbal and spatial skills throughout the cycle. However, studies on PMS and PMDD have only looked into changes in executive function and attention.

What’s to come?

Your brain on hormones

As of 2024, Elle Murata, a PhD candidate at UC Santa Barbara’s Jacobs Lab, is looking more closely at the impact of ovarian hormones on brain morphology. From reproductive disorders, such as endometriosis, to early-onset menopause, the Jacobs Lab is focusing on changes to typical hormonal fluctuations through a “dense-sampling” method.

Murata explained that this “dense-sampling” method looks at only a few individuals, but at far more time points over the course of days to years. This is different from more traditional methods of collecting endocrine data, which typically acquire data at one or a few timepoints. Dense sampling designs provide a more detailed view into crucial hormonal transition periods in a woman’s lifespan by collecting data at many timepoints within these transition periods, offering far more precision than we’ve previously had access to.

Hormones 101: Why sex hormones are important for everyone, regardless of gender

If we’re going to take a closer look at women’s brain health across the menstrual cycle, it’s important to establish an understanding of how the male brain changes across a comparable biorhythm. This led Murata and her colleague, Hannah Grotzinger, to conduct a study showing that women’s brains aren’t the only ones affected by sex hormone fluctuations. Their analyses revealed that fluctuations in testosterone and estrogen impact men and women’s brains to a similar extent.

The authors found that peaks in testosterone, estrogen, and cortisol are associated with higher ‘whole-brain coherence’, which measures how well different brain regions are synchronized. For men, steroid hormones and coherence are high in the morning and decrease throughout the day. These findings challenge the widely-held belief that fluctuations in sex hormones only impact the female brain, when in reality they are crucial for brain function in both sexes.

Brains, Bleeding, and Bloating—How can women use this knowledge of brain and hormonal changes to understand menstrual symptoms?

I asked Elizabeth if there were findings from the study that surprised her.

“For some of the individual findings, you can see some people trend opposite of the group.”

This observation reveals that biometrics and symptoms don’t always align with what is considered “normal”. As Elizabeth said,

“Everyone has different emotional and cognitive experiences. There’s a lot of individual differences throughout your experience of the cycle and hormone fluctuation.”

Rizor shared personally about her own experience as a naturally cycling woman and the pressure she felt from herself and others to ignore her cycle symptoms:

“Throughout my life, I didn’t think critically often enough about my menstrual cycle, just that it was a kind of nuisance I had to deal with. I also felt pressure to stay normal and perform the same every single day. What I think our study does well, as do some other studies, is that it literally shows there are baseline anatomical changes that are fairly consistent across a group of around 30 women.”

And, these changes do not exist in isolation.

“These hormones are circulating in the blood throughout your entire body, so they’re not just going to be affecting your reproductive organs, or your abdomen. These hormones cross the blood-brain barrier and go into the brain. There could be other effects on other organs as well—so it’s really a whole body process.”

There’s reassurance in remembering we don’t have to feel alone in our experiences—tuning in and recognizing our symptoms can provide opportunities to connect with others. There is no shame in experiencing these symptoms. Our task now is to understand these changes and figure out what our bodies are telling us.

“We can all experience our own symptoms and be used to having them in our day-to-day lives. On certain days during my PMS phase, I get more moody and bloated. But I think we often feel that we’re alone in our experiences. But you don’t actually know if—if you don’t talk about it—what other people are also experiencing. You might not make the link that these things are happening because of baseline biological processes.”

From Menses to Mindfulness: Connecting with Your Cycling Brain

With all of the conflicting health information available online—it’s easy to get lost and confused about what to do. What Elizabeth and her fellow researchers at UCSB are discovering, is that women have natural neuronal fluctuations. These fluctuations may correlate with differences in how our bodies feel throughout the month. Instead of continuing to disconnect and place generalized expectations on ourselves, let’s tune back in and give our bodies what they actually need—a listening ear and response to its signals.

This article uses ‘women’/‘men’ and ‘male’/‘female’ to describe people assigned female/male at birth to reflect the language of the studies cited. We acknowledge that gender identity and gender assigned at birth do not always align and we’re hopeful for future health research that includes everyone.