Chapter 1: The History of Hysteria

Welcome to the Guava Community Book Club! Before we get started, I should introduce myself. I’m June, the Head of Content and Science Writer here at Guava. I have a background in science and a knack for explaining things, so I combined the two and find myself before you today.

A bit of background

With the release of Guava's new cycle-tracking features, we've sparked some excitement in the reproductive health space. While developing this tool, we encountered plenty of the biases and misconceptions that are ingrained in women’s health.

Here are a couple examples of what I mean: 28-day cycles aren’t that common and nearly a quarter of those who menstruate experience irregular periods. We realized that existing cycle trackers weren't catering to those with irregular cycles caused by chronic conditions, and many paywalled valuable information about cycle history.

Driven by our belief that everyone deserves access to easy, free, and comprehensive health tracking, we built a cycle tracker that addresses these issues. However, cycle tracking is just one piece of the puzzle. As part of our broader mission to make health information accessible, we wanted to create an approachable way for people to learn about the biology and history of reproductive health. That's where Dr. Tang's book comes in, offering invaluable insights into the often overlooked aspects of women's health history.

As a science communicator and enthusiast, I'm excited to share my thoughts on Dr. Karen Tang's It's Not Hysteria, which the Guava Community Book Club has recently begun reading.

Hysteria at First Glance

Dr. Tang begins our journey by delving into the history of the word, “hysteria.” She waits a couple of pages to reveal that the word itself is derived from the Greek word for uterus, hystera. While this connection was common knowledge to some, like our Head of Product Isabel, it came as a surprise to many of us who haven’t always been so deeply immersed in reproductive health issues.

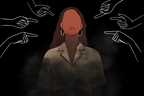

“This word, hysteria, contains all the judgments and assumptions about female bodies that have existed for thousands of years.”

So medical bias runs deep—really deep. In fact, we've barely scratched the surface. From my perspective, it all boils down to one troubling notion: women being blamed for their own pain.

Frustrated Uteri, Wandering Wombs, and the History of Hysterectomies

Dr. Tang reveals that historically, "frustrated uteri" were blamed for the myriad problems—both physical and psychological—that women face. Initially, physicians attributed this frustration to a lack of sexual activity. They believed the uterus craved pregnancy and, when unfulfilled, wreaked havoc on the female psyche. This phenomenon was referred to as the “wandering womb.” Fast forward a couple hundred years and a new hypothesis emerged: women's health issues stemmed from too much sexual activity—but only the selfish kind, naturally. Masturbation became the new culprit. God forbid women enjoy anything.

Dr. Tang then explains that, with little to no medical evidence, doctors resorted to hysterectomies (uterus removal surgeries) and—even more shockingly—clitoridectomies (clitoris removal surgeries) to "cure" hysteria. These procedures were performed frequently until their low success rates and high mortality rates forced doctors to reconsider their approach. Surprise, surprise: it turns out the clitoris doesn't actually drive women insane.

Today, many medical conditions can be effectively treated by removing the uterus. However, this raises an issue that is needlessly complex: women's autonomy over their reproductive futures. Dr. Tang delves into a common predicament faced by people with uteri—doctors often refuse to perform hysterectomies on those who want (or need) them, citing the possibility that the patient might want to get pregnant in the future. This paternalistic approach leaves patients in pain and frustrated, unable to make decisions about their bodies.

“It’s hard to imagine a non-gynecological medical scenario where physicians would tell competent adult patients that they don’t actually know their goals and therefore can’t make decisions about their health.”

Hysterical Women in Literature

Dr. Tang proceeds to highlight an intriguing tidbit of Charlotte Perkins Gilman's famous short story, "The Yellow Wallpaper." In this haunting tale, a woman is treated by her physician husband for an undefined feminine mental illness—essentially, hysteria. Her prescribed treatment involves constant surveillance and a prohibition on any mentally stimulating activities. As the story unfolds, the protagonist increasingly perceives a woman trapped within the wallpaper. By the end, she frees this woman by frantically tearing the paper from the walls.

This highlights a recurring theme among female authors who have experienced "the paternalistic management of female patients," as Tang aptly describes it. For me, Sylvia Plath's The Bell Jar comes to mind. In her only novel, Plath vividly portrays her descent into mental illness. During this journey, she's placed under the watchful eye of a male doctor, eerily similar to the husband/doctor in "The Yellow Wallpaper." Both stories feature treatments centered on prolonged isolation and enforced "rest." In reality, these women weren't receiving legitimate treatment—they were simply being silenced and removed from society.

All this discussion of young women descending into quiet madness begs the question: why? Could it be that society has undermined female pain and silenced their voices to the point of driving them to literal insanity? Maybe.

On Race

Moving right along, Dr. Tang introduces our next topic: racism in healthcare. We first meet James Marion Sims, the doctor who pioneered some of the first truly productive gynecological care. But it doesn’t take long for things to turn sour.

“Until recently, the medical community and general public didn’t know that he [Sims] had developed several of his surgical techniques by operating on un-anesthetized, enslaved Black women.”

This turn of events, although horrifying, is unsurprising, to say the least. When I was an undergraduate at UC Santa Barbara, I took an oncogenesis (cancer) class with Dr. Meghan Morrissey. In my final weeks of college, she became my first biology professor to discuss the deeply rooted racism that prevails in the medical system. In her lecture, she cited Harriet Washington, a writer, medical ethicist, and lecturer at Columbia. Washington illustrates that due to the horrifying reality of medical experimentation (including neglect, lack of consent, and underestimation of pain thresholds),

“No one can dismiss Blacks’ historically grounded fear of [medical] research and retain credibility…We have to reckon with that history before we can talk about changing things.”

According to Mass General Brigham, “Black women who develop breast cancer are about 40% more likely to die of the disease than white women.” But make no mistake—this discrepancy shouldn’t be attributed to Black people being reluctant to seek treatment, nor is it because of some inherent difference in Black tumor biology. Dr. Morrissey shed light on the main issues from a research standpoint.

- Under-enrollment of diverse patients in clinical trials, the patients of which tend to have lower mortality rates. Clinical trials provide patients with the newest, most cutting-edge treatments in cancer biology, but they tend to occur in well-funded hospitals in wealthy socioeconomic areas.

- The less diverse a sample population is, the less confident we are that the treatment can be generalized to other populations. When researchers found a groundbreaking genetic marker for breast cancer, it turned out to be only 1/3 as accurate in Black women, contributing to comparative diagnostic delays. To put it simply, Dr. Morrissey noted:

“Algorithms based on European ancestry will be better predictors for patients of European ancestry”

But these points only pertain to the research side of things. Dr. Tang reminds us that there are long-standing cultural biases regarding Black pain perception that persist today, affecting pain treatment during healthcare administration.

“A 2016 study showed that half of the medical students and residents polled believed that Black people had less sensitive nerve endings, thicker skin, and lower perception of pain than white people, which has no basis in scientific fact.”

As if we haven’t been sufficiently baffled yet, this metric will do the job. It’s a grave reminder that racial bias finds its roots alongside the same historical context that built the medical system. These biases will remain unless action is taken to dismantle them and educators like Dr. Morrissey, Harriet Washington, and Dr. Tang are graciously taking the first steps.

The Bottom Line

I could clearly go on, but I unfortunately have to keep the length of a modern attention span in mind. I’ll wrap this up by saying that Dr. Tang has opened a real can of worms for me.

In just the first chapter, she illuminates the deep-seated biases in reproductive healthcare—from antiquated notions of "wandering wombs" to the stark racial disparities in medical treatment that persist today. Her work serves as a potent reminder that the struggle for equitable healthcare is far from over. As we move forward to improve global health, it's crucial that we challenge biases and strive for a healthcare system that truly serves everyone.