This is article seven in a seven-part series addressing gender bias in the healthcare system.

As this article series comes to a close, I leave us with a very important ending topic, one that calls for perspective. It would be unfair to discuss women in the healthcare system without mentioning those who experience this system every day, our female medical professionals. After reading much about provider bias, it's easy to get wrapped up in the notion that doctors are the problem. So, to turn the tables, we will discuss how patients can often discriminate as well.

Title and Position

To begin the conversation, I will loop back to a point I made in my very first article: the issues with mislabeling. Let's use my former example, "Nurse, can you fluff my pillow?"

Aside from the lack of please and thank you, this comment is hardly harmful when said to a nurse. After all, it's their job, and they are probably happy to help. However, when said to an experienced female doctor, there's suddenly a lot more weight behind the phrase.

First of all, mistaking a female doctor for a nurse is a common problem. In one study of 4000 British citizens, only 5% predicted their doctor to be female, while 63% predicted their nurse to be female. Dr. Kathleen McGraw, MD, Chief Medical Officer of Brattleboro Memorial Hospital, has experienced this herself many times. Even after introducing herself as Dr. McGraw, some patients still don't realize she's their doctor, and Dr. McGraw warns it then becomes hard to gain authority. If patients don’t recognize her station, they may start to question treatments she recommends, undermine her, and fail to uphold the same respect as they would for a male doctor.

Similarly, she found that many patients address her by her first name or patronizing pet names like "honey" and "dear" instead of her title. From an outside perspective, it can be hard to see why this is a problem. But let's think about it, you've probably never called your male provider "sweetheart," so why do many people feel inclined to say this to their female provider?

Calling your provider by their first name again undermines their authority. Doctors, especially, need patients to recognize their position. They avoid casual relationships with patients for a reason. The esteem of their position tells patients they are knowledgeable enough to make important decisions.

Additionally, female doctors are often asked to perform tasks well below their license, like fetching a cup of coffee or propping a pillow, which can lead to inefficiency within the office. As Dr. McGraw put it,

She explained that women in the field constantly have to question tasks given to them. Often, they find themselves wondering if it's really just a coincidence that the older male physician asked them specifically to fetch a blanket instead of their male counterparts.

The Wage Gap

As a feminist constantly finding myself wrapped up in debates around women's rights, there's always one thing that constantly gets brought up, the gender pay gap. People can argue about this topic forever, whether they think the pay gap is because men have a better work ethic (quite doubtful), maternity leave, systemic issues, or just clear-as-day bias. But, whatever you may believe, the gender pay gap definitely exists, and I'll throw a stack of peer-reviewed research articles at anyone who disagrees. So, it should be no surprise this pay gap also occurs in the medical field.

A meta-analysis from 2021 of 46 different research articles found that almost all of the studies observed a large pay difference between male and female doctors, often a gap that spanned thousands of dollars each year.

When talking to an Intensive Care Nurse, the pay gap was the first thing she brought up. She made the point that nursing is a female-dominated agency, and yet, women are still paid less. From discussing salary with her coworkers, she learned that, even with a higher level of education, she was still earning less than her male counterparts.

So then, what is causing this pay gap?

Well, Dr. McGraw brought up two interesting points that she believes contribute to the lower pay for female doctors specifically.

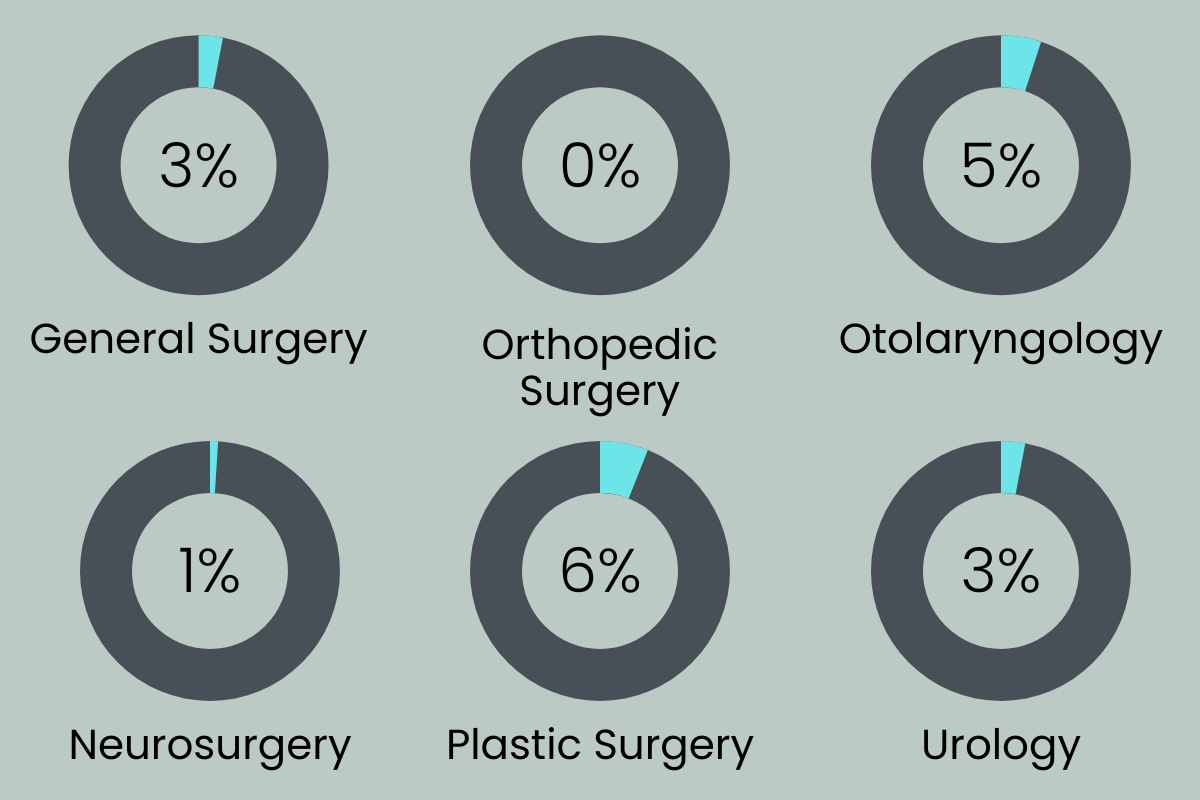

Firstly, there’s a lack of female leadership in medicine. Studies from 2014 and 2017 show that women make up 3% of Department Chairs and 10% of Program Directors in General Surgery Residencies, 1% and 3% in Neurology, and 7.3% of Division Chiefs in Gastroenterology fellowships.

But why do men hold most of the leadership positions in medicine? Besides employer bias, one reason is that our society is not built in a way that easily allows women to be both mothers and professionals.

Dr. McGraw pointed out. And she's right. Mothers generally do around 1.9 times the amount of household work fathers do. In households where both parents work, wives still do an average of 13-16 hours per week of household work, while husbands average around 6-8 hours per week. Even more shockingly, in households where women make an equal or higher salary than their husbands, they are still contributing more to household chores.

Let’s face it, growing up, it was usually our mothers who had to run to the store to grab supplies for our second-grade science fair projects, stay home from work with us when we were sick, and leave work early to drop off the homework we accidentally left in their car that morning.

The truth is mothers don't stop working after they leave the office, not when most of the household duties rest on their shoulders. And because female doctors aren’t exempt from this reality, they don't have time to pick up quality improvement projects or other assignments that usually launch people into leadership roles.

Additionally, fewer women in leadership positions mean fewer women serving as mentors for other women. Mentors can provide psychological support, cultivate self-confidence, encourage talent, and overall give their mentees an edge in the field. Therefore, without mentors for women in medicine, the cycle thus repeats itself.

Another possible reason for this wage gap is a lot more complicated than you’d expect. Physicians' income is driven by the number of patients they can see in a year, and bias can play a role in this number. You may have noticed throughout the series most women I talked to who had been gaslit and ignored by their male physicians ended up switching to a female doctor or an all-female team. But why is this the case? Well, women are thought of as nurturers, as more compassionate and accommodating than men.

As great as those qualities are, they can be a burden in the professional world. Patients with complex issues gravitate towards a more caring, accommodating doctor. For example, someone with an ear infection probably doesn't care which doctor they get. It's a quick appointment, and not much needs to be discussed. But someone trying to understand an undiagnosed and complicated issue seeks out doctors they feel will listen and truly care. So they ultimately gravitate toward female doctors (whether the stereotype is true or not).

But what people don't understand is that complicated patients tend to take longer than a physician's allotted appointment time. Therefore, a doctor with multiple time-consuming patients must lower the number of patients they see in a day to still stay on schedule, which ultimately lowers their pay.

One study found that female primary care physicians (PCPs) spend an average of 16% more time with patients per appointment than male PCPs do. They also schedule fewer patients over the span of a year.

But, of course, this extra time isn't the patient's fault. Patients deserve to be heard, and complex problems cannot be solved in 15 minutes. Instead, we can blame the faulty structure this system is built upon.

These problems are just the tip of the iceberg for this topic. There are far more hurdles our female medical staff face every day. For example, in 2016, a survey found that 30% of female academic medical faculty experienced sexual harassment in their field. Additionally, the average maternity leave for residents is only around six weeks. Both examples serve to show how much more progress needs to be made.

This series doesn't even begin to cover all the other demographics that also face discrimination in the healthcare system, like people of non-binary genders, people of color, those of low socioeconomic status, and more. Like every other aspect of our society, there's room for improvement for providers, patients, and every role in between. We cannot grow as a society if we refuse to recognize its flaws. And recognizing these imperfections is one step closer to changing them.

So next time your female doctor asks you to call her by her title, don’t take it personally or assume she’s being pretentious. Ask yourself instead if maybe there’s more to it, if maybe this simple request is the turning point of perspective you didn’t even know you needed.